March 25, 2018, is the 107th Anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York’s Greenwich Village. This tragedy took the lives of 146 young immigrant garment workers and galvanized a reform movement to raise standards for workers.

March 25, 2018, is the 107th Anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York’s Greenwich Village. This tragedy took the lives of 146 young immigrant garment workers and galvanized a reform movement to raise standards for workers.

At UNITE HERE’s headquarters in New York, staff and members will gather to remember the victims with a reading of their names and testimony from one of the survivors. The ceremony will be accompanied by a special display in the union building lobby at 275 7th Avenue, located in the heart of New York’s Garment District.

To learn more about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, visit Cornell University’s Kheel Center.

This incident has had great significance to this day because it highlights the inhumane working conditions to which industrial workers can be subjected. To many, its horrors epitomize the extremes of industrialism.

“It is by remembering our past that we prepare to fight for our future. We are measured by how we protect the most vulnerable and ensure their health and safety to pursue life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, that is our guiding light.”

—D. Taylor, President, UNITE HERE

The tragedy still dwells in the collective memory of the nation and of the international labor movement. The victims of the tragedy are still celebrated as martyrs at the hands of industrial greed.

The fire at the Triangle Waist Company in New York City is one of the worst disasters since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The Asch Building was one of the new “fireproof” buildings, but the blaze on March 25th was not their first. It was also not the only unsafe building in the city.

On the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, fire fighters struggle to save workers and control the blaze. The tallest fire truck ladders reached only to the sixth floor, 30 feet below those standing on window ledges waiting for rescue. Many men and women jumped from the windows to their deaths. Photographer: unknown, March 25, 1911.

An officer stands at the Asch Building’s 9th floor window after the Triangle Fire. Sewing machines, drive shafts, and other wreckage of the factory fire are piled in the center of the room. Photographer: Brown Brothers, 1911.

In the April 5th funeral procession for the seven unidentified fire victims, members of the United Hebrew Trades of New York and the Ladies Waist and Dressmakers Union Local 25, International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, the local that organized Triangle Waist Company workers, carry banners proclaiming “We Mourn Our Loss.” Photographer: unknown, April 5, 1911.

The Triangle Fire Memorial to the six unidentified victims in the Evergreens Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY, was created in 1912 by Evelyn Beatrice Longman. The six bodies were all recently identified by Michael Hirsch, who worked tirelessly to recognize the names of the unidentified victims.

The victims names:

• Lizzie Adler, 24

• Anna Altman, 16

• Annina Ardito, 25

• Rose Bassino, 31

• Vincenza Benanti, 22

• Yetta Berger, 18

• Essie Bernstein, 19

• Jacob Bernstein, 38

• Morris Bernstein, 19

• Vincenza Billota, 16

• Abraham Binowitz, 30

• Gussie Birman, 22

• Rosie Brenman, 23

• Sarah Brenman, 17

• Ida Brodsky, 15

• Sarah Brodsky, 21

• Ada Brucks, 18

• Laura Brunetti, 17

• Josephine Cammarata, 17

• Francesca Caputo, 17

• Josephine Carlisi, 31

• Albina Caruso, 20

• Annie Ciminello, 36

• Rosina Cirrito, 18

• Anna Cohen, 25

• Annie Colletti, 30

• Sarah Cooper, 16

• Michelina Cordiano, 25

• Bessie Dashefsky, 25

• Josie Del Castillo, 21

• Clara Dockman, 19

• Kalman Donick, 24

• Nettie Driansky, 21

• Celia Eisenberg, 17

• Dora Evans, 18

• Rebecca Feibisch, 20

• Yetta Fichtenholtz, 18

• Daisy Lopez Fitze, 26

• Mary Floresta, 26

• Max Florin, 23

• Jenne Franco, 16

• Rose Friedman, 18

• Diana Gerjuoy, 18

• Molly Gerstein, 17

• Catherine Giannattasio, 22

• Celia Gitlin, 17

• Esther Goldstein, 20

• Lena Goldstein, 22

• Mary Goldstein, 18

• Yetta Goldstein, 20

• Rosie Grasso, 16

• Bertha Greb, 25

• Rachel Grossman, 18

• Mary Herman, 40

• Esther Hochfeld, 21

• Fannie Hollander, 18

• Pauline Horowitz, 19

• Ida Jukofsky, 19

• Ida Kanowitz, 18

• Tessie Kaplan, 18

• Beckie Kessler, 19

• Jacob Klein, 23

• Beckie Koppelman, 16

• Bertha Kula, 19

• Tillie Kupferschmidt, 16

• Benjamin Kurtz, 19

• Annie L’Abbate, 16

• Fannie Lansner, 21

• Maria Giuseppa Lauletti, 33

• Jennie Lederman, 21

• Max Lehrer, 18

• Sam Lehrer, 19

• Kate Leone, 14

• Mary Leventhal, 22

• Jennie Levin, 19 • Pauline Levine, 19

• Nettie Liebowitz, 23

• Rose Liermark, 19

• Bettina Maiale, 8

• Frances Maiale, 21

• Catherine Maltese, 39

• Lucia Maltese, 20

• Rosaria Maltese, 14

• Maria Manaria, 27

• Rose Mankofsky, 22

• Rose Mehl, 15

• Yetta Meyers, 19

• Gaetana Midolo, 16

• Annie Miller, 16

• Beckie Neubauer, 19

• Annie Nicholas, 18

• Michelina Nicolosi, 21

• Sadie Nussbaum, 18

• Julia Oberstein, 19

• Rose Oringer, 19

• Beckie Ostrovsky, 20

• Annie Pack, 18

• Provindenza Panno, 43

• Antonietta Pasqualicchio, 16

• Ida Pearl, 20

• Jennie Pildescu, 18

• Vincenza Pinelli, 30

• Emilia Prato, 21

• Concetta Prestifilippo, 22

• Beckie Reines, 18

• Louis Rosen (Loeb), 33

• Fannie Rosen, 21

• Israel Rosen, 17

• Julia Rosen, 35

• Yetta Rosenbaum, 22

• Jennie Rosenberg, 21

• Gussie Rosenfeld, 22

• Emma Rothstein, 22

• Theodore Rotner, 22

• Sarah Sabasowitz, 17

• Santina Salemi, 24

• Sarafina Saracino, 25

• Teresina Saracino, 20

• Gussie Schiffman, 18

• Theresa Schmidt, 32

• Ethel Schneider, 20

• Violet Schochet, 21

• Golda Schpunt, 19

• Margaret Schwartz, 24

• Jacob Seltzer, 33

• Rosie Shapiro, 17

• Ben Sklover, 25

• Rose Sorkin, 18

• Annie Starr, 30

• Jennie Stein, 18

• Jennie Stellino, 16

• Jennie Stiglitz, 22

• Sam Taback, 20

• Clotilde Terranova, 22

• Isabella Tortorelli, 17

• Meyer Utal, 23

• Catherine Uzzo, 22

• Frieda Velakofsky, 20

• Bessie Viviano, 15

• Rosie Weiner, 20

• Sarah Weintraub, 17

• Tessie Weisner, 21

• Dora Welfowitz, 21

• Bertha Wendroff, 18

• Joseph Wilson, 22

• Sonia Wisotsky, 17

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Tonight, Congresswoman Jacky Rosen (NV-03) will attend the State of the Union with Nevada Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipient and Culinary Workers Union Local 226 member Nery Martínez. Mr. Martínez fled to the U.S. from El Salvador in the 1990s and lives in Las Vegas. Mr. Martinez works as a bar apprentice at Caesars Palace Hotel and Casino. Martinez’s wife is also a TPS holder from El Salvador, and he is the father of two children who are U.S. citizens. Earlier this month, the Trump Administration announced plans to end TPS for about 200,000 Salvadorans.

“Nery came to the U.S. years ago and has worked tirelessly to build a better future for himself and his family in Nevada,” said Rosen. “I’m honored to have him as my guest for the State of the Union. The President and this Congress need to be reminded that his callous and misguided decision to end the TPS program will have very real consequences, destroying thousands of families like Nery’s who have played by the rules and contributed so much to our communities and our economy.”

“My contributions to the United States and Nevada are not temporary,” said Martínez. “I pay into social security benefits, pay taxes, and provide for my family. I hope casino companies will stand up for their TPS employees who work hard every day and will not be silent while we are at risk. Nevada is our home and we are here to stay.”

Read the rest of the release >>

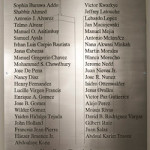

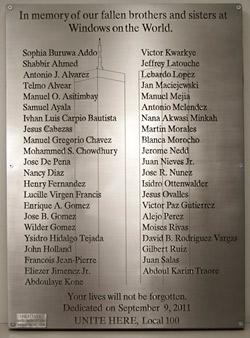

On the 17th anniversary of September 11, 2001, UNITE HERE remembers all those who lost their lives on that tragic day. We hold especially close the memory of our 43 sisters and brothers from UNITE HERE Local 100 who died while working at Windows on the World, a restaurant located at the top of the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

On the 17th anniversary of September 11, 2001, UNITE HERE remembers all those who lost their lives on that tragic day. We hold especially close the memory of our 43 sisters and brothers from UNITE HERE Local 100 who died while working at Windows on the World, a restaurant located at the top of the North Tower of the World Trade Center.